The condemned villages of the West Bank

Nobel literature prizewinner Mario Vargas Llosa offers a first-hand account of life in the Palestinian villages as they struggle against Israeli occupation

“Israel has one big problem – the settlements in the West Bank. In other words, the Occupied Territories,” Yehuda Shaul tells me. “Next year, it will be half a century since they began their occupation of Palestinian land. But there’s a solution and I’m going to see it implemented before I die.”

I tell my Israeli friend that it takes real optimism to believe that the 370,000 Israeli settlers who have created a veritable Bantustan, fencing in 2,700,000 Palestinians and isolating one Palestinian city from another, will withdraw from the West Bank in the name of peace anytime soon.

But Yehuda, who works tirelessly to highlight the plight of the West Bank Palestinians that so many of his compatriots are determined to ignore, tells me I might be less skeptical after our trip to the Palestinian villages in the mountains south of Hebron.

By increasing the number of settlements, the two-state solution becomes impossible, whatever Israeli leaders pretend to accept on paper

The last time we were in those mountains together was six years ago. At that time, the village of Susiya had a population of 300 and seemed doomed to disappear like so many of its neighbors. Now, it has a population of 450 because many families that fled have returned and, like Yehuda, they are feeling optimistic despite the atrocities.

The aggressions that Susiya and neighboring villages have been subjected to for so long haven’t ceased. Far from it. Locals show me the rubble of houses recently demolished, water wells blocked with rocks and rubbish, trees cut down by settlers and videos they were able to make of settlers attacking the villagers with truncheons and other weapons, as well as the arrests and abuse carried out by the Israeli Defence Forces (IDF).

In the communal house that Nasser Nawaja uses to carry out his duties as unofficial mayor, I am shown the demolition orders that, like the swords of Damocles, threaten the few buildings still standing. It looks official: this area has been chosen for military maneuvers by the IDF and the villages have to go, though not the settlements or the settlers’ proliferating outposts.

Sometimes the excuse is that the Palestinians’ houses have been put up without building permits. “It’s madness,” Nasser tells me. “When we ask for permission to build or reopen the wells, they say no. And then they knock down the houses for being built without permission.”

In this village, as in so many others, the residents – farmers and shepherds – don’t live in houses as such. Their precarious dwellings are made from canvas and tin cans. Or else they live in some of the numerous caves in the area that have so far escaped being blocked with rocks and rubbish by the soldiers.

In spite of everything, the people in Susiya and Yimba – the two villages I visited – are still there, resisting the abuse with the support of several NGOs and Israeli solidarity groups such as Yehuda’s Breaking the Silence.

I met an extremely nice young Jewish man in Susiya named Max Schindler, an American who had come as a volunteer to teach the local children English for a few months. His reasons were clear: “I wanted them to see that not all Jewish people are the same,” he said.

In fact, there are many others like Max who are helping the Palestinians file claims in the courts, who are vaccinating their children and protesting the abuse. Among them there are writers like David Grossman and Amos Oz, who sign manifestos and mobilize the public to demand that authorities halt the aggressions and allow the Palestinians to live in their villages in peace.

One such protest, held a few months ago, has temporarily saved the ancient village of Yimba, although not before the demolition of 15 homes. Its fate now hangs in the balance, awaiting a definitive decision from the Supreme Court. Yimba has an enormous cave, so far untouched, which I am told dates back to the Roman era when the village was on the pilgrims’ route to Mecca – you can still see traces of the path streaking through the stony desert. At that time Yimba was a prosperous town with many shops and restaurants. Now, its archaeological importance offers the Israeli authorities a new excuse for evacuating the villagers.

It’s the same story I heard in Susiya. “The minute they manage to get rid of us on that pretext, the settlers will move in. Of course, there is no problem with them living on top of archaeological remains.”

As in Susiya, I am surrounded by skeletal, barefoot children who are brimming with excitement. There’s one girl in particular, with a naughty glint in her eye, who cracks up laughing at my attempts to pronounce her name in Arabic.

One need only take a look at a map to see the bigger picture behind the location of the settlements in the Occupied Territories. They cut off all the big Palestinian cities from each other, hindering communication and movement – fragmenting the territory to such as extent that a future Palestinian state in the West Bank becomes an impractical proposition.

No one can fail to see the deliberate strategy here. By increasing the number of settlements, the two-state solution becomes impossible, whatever Israeli leaders pretend to accept on paper. Why else would all Israel’s governments, whether right, center or left (with the sole exception of the last Ariel Sharon administration, who removed settlements from the Gaza strip in 2005) have allowed the systematic growth of illegal Israeli settlements on Palestinian territory, a constant source of friction fuelling Palestinian fears that their presence is being whittled away?

I don’t pretend to be able to read the minds of Israel’s political elite, but you only have to follow the developments of the last few decades, including the famous “Sharon Wall” or Israeli West Bank Barrier, to know that there is a specific policy at work. Far from tackling the occupation, the latter is being encouraged and protected.

Sign up for our newsletter

EL PAÍS English Edition has launched a weekly newsletter. Sign up today to receive a selection of our best stories in your inbox every Saturday morning. For full details about how to subscribe, click here.

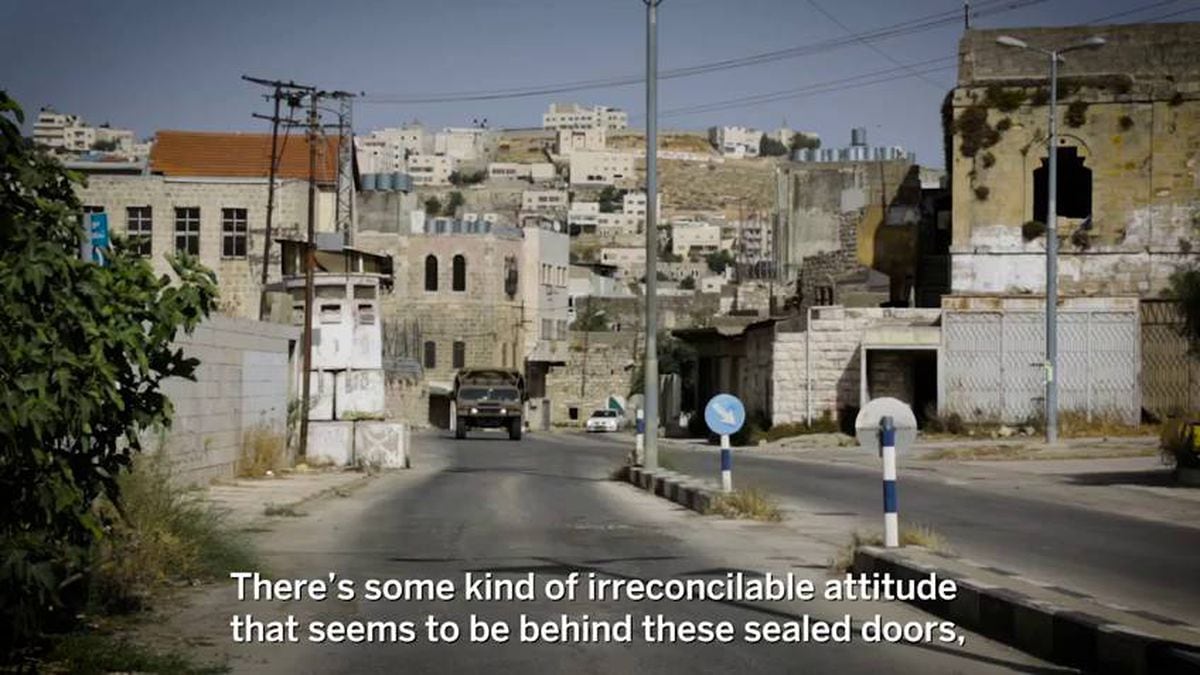

Of all the settlements, the most shocking ones are the five established within the city of Hebron. These contain 850 Israeli settlers living alongside, but sealed off from, 200,000 Palestinians. To protect these settlers from the people they have invaded, 650 Israeli soldiers have been deployed to what is now little more than a ghost town with its “sterilized” streets, its closed shops and front doors; a city with no soul. I wandered these dead streets 11 years back and the only thing that has changed is that the racist anti-Arab graffiti scrawled on the walls is gone.

What hasn’t gone are the police checkpoints that, among other things, make sure Palestinians do not travel through the city by car. This means they have to make an enormous detour to get from one neighborhood to another. The four Israelis who accompany me say that the worst thing is that no one even talks about the horror of Hebron anymore, or about the tremendous injustices being committed against 200,000 residents in order to protect 850 invaders.

English version by Heather Galloway.